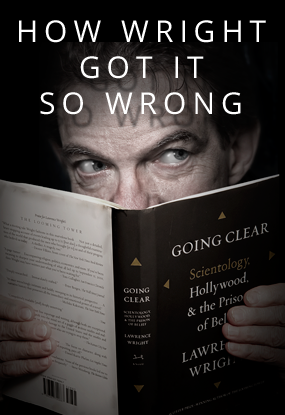

A Correction of the Falsehoods in Lawrence Wright's Book on Scientology

“Word Arrived while the Apollo was in dry dock in Portugal that the French government was going to indict the Church of Scientology for fraud, with Hubbard named as a conspirator (he would eventually be convicted in absentia and sentenced to four years in prison).

Hubbard flew to New York the very next day.”>> True Information: Mr. Norman Starkey, who was the Captain of the Apollo at the time of Mr. Hubbard’s departure to New York wrote that Mr. Hubbard was not even aboard the Apollo when it was in dry dock in Lisbon and that his trip to New York was for the purpose of conducting a sociological study. Mr. Starkey wrote:

“1. Mr. Hubbard was not even aboard the Apollo when she was in the Lisbon dry dock in October 1972. He remained ashore in his villa in Tangiers and told me that he was going to concentrate on some research while I took the ship up to Lisbon and would oversee the refit and renovations to upgrade several areas of the vessel.

2. At that time, L. Ron Hubbard traveled to the U.S. to continue his researches into society. While on this trip, and as a direct result of his work in New York, Mr. Hubbard developed the Volunteer Ministers Program, one of the largest and most successful international disaster relief and humanitarian programs in the world today. That was just one of his many research developments at that time.”

The case itself was an injustice that was ultimately won after a ten-year battle.

L. Ron Hubbard had never been served with a suit, had never been informed about the charges that were brought against him and had never performed any activities of any sort in France. The decision concerning Mr. Hubbard was not appealed because to do so would have necessitated that he go to France and subject himself to the whims of Napoleonic authority.

Mr. Hubbard’s popularity waned not in the least in France as a result of it all -- neither as a writer nor a humanitarian. In the decade following the mock trials, he personally received prestigious awards from French literary circles while the number of Scientology churches and missions more than doubled. France accounts for more recognitions and awards to L. Ron Hubbard than any other country in Europe.

That case grew out of a French police report on Scientology in 1970 that was copied directly from the 1968 report on Scientology by UK’s Scotland Yard.

The Church had no trouble with the government in France prior to 1970. The trouble began coincident with the flow of false reports from England.

That the French authorities had no information about Scientology or L. Ron Hubbard prior to communicating with the British is clear from the first French report on Scientology, written by police adjutant Jean-Claude Mission. This report led directly to the fraud case mentioned above. The report is titled “Information on the (criminal) movements of the ‘SCIENTOLOGY’ sect, 58 rue de Londres, in PARIS 8.” It was written some time between July 8 and November 2, 1970, when the Police Commissioner sent a copy to the public prosecutor’s office.

Mission’s report stated the following, referring to the activities at 58 rue de Londres (the situs of the Church of Scientology at the time):

“Every day of the week, without exception, meetings are held…. It has not been possible to obtain the least bit of information on the aim of these daily meetings.”

“In France, he [Mr. Hubbard] is unknown to the different police services.”

In other words, prior to their receipt of information from overseas, the French authorities possessed no negative information of any kind concerning either Scientology or its founder. According to Mission’s report, on July 8, 1970, “an unknown person wrote to the Parquet de Paris denouncing the (criminal) movements of a religious sect called Scientology established in Paris….” Since Mission had no data on Scientology or Mr. Hubbard, Mission notes in his report that he checked with INTERPOL and the British authorities.

In fact, on August 18, 1970, INTERPOL Paris telexed INTERPOL London and INTERPOL Copenhagen indicating that an investigation was in progress regarding Mr. Hubbard and requesting any information concerning the executives of the Church at Saint Hill and in Copenhagen. On September 4, 1970, INTERPOL London replied to INTERPOL PARIS and enclosed a report on Scientology. This is certainly the report of September 26, 1968, by the Criminal Investigation Department of the Metropolitan Police at New Scotland Yard, since Mission’s report repeated much that was in the Scotland Yard report.

Indeed, on October 10, 1975, INTERPOL Paris National Central Bureau wrote to INTERPOL London stating that the Scientology organization was under investigation and noting that “your report of 4.9.70 has been largely quoted in the report put together by the … prefecture of police addressed to the magistrate of instruction.”

A comparison of Mission’s report and the Scotland Yard report shows – some minor differences due to translation variables aside – that it was indeed Scotland Yard’s report that Mission relied upon and copied from.

The French authorities, with no information of their own, assumed that it was true what England’s government was telling them; they simply took over and parroted the falsehoods about Scientology and its founder being circulated by the British.

A judicial inquiry was opened and led directly to a criminal investigation being ordered on December 16, 1970, resulting in a fraud case brought against three officials of the French Church of Scientology and L. Ron Hubbard.

On the 10th of March, 1971, the Church was raided by the drug squad. No drugs were found. However, the parishioners and staff who were in the premises were arrested and harassed. The charges could not be substantiated and the Scientologists were released after hours. The case was dormant until a police officer, in 1972, compiled a report on Scientology for which he used the files of the French police. Contained in those files were false reports from overseas that had been sent to France via Interpol, which had been exposed by the Church for its crimes and Nazi connections. Based solely on this report, the investigation was revived. Two negative psychiatric expertises were commissioned by the police which lent further impetus to their objective to set the Church up.

The investigation was kept alive for seven years with false reports, phony, expertises and false accusations. In summer, 1977, the case was sent to trial with four defendants: three past and present executives of the Church in France and, despite the fact that he had never lived in France nor had any relationship with the plaintiff, L. Ron Hubbard.

The trial, recognized by experts as a mockery of justice based on the antiquated principles of the Napoleonic justice system, found the four defendants guilty of fraud. Three of them, including Mr. Hubbard, were judged in absentia and convicted in February, 1978. The three French church executives appealed the verdict and stood trial in France. They were all acquitted. In each one of these appeals, the Church was acknowledged as a religion and the charges of fraud completely dropped. Mr. Hubbard passed away during the pendency of the challenge to his conviction, mooting it. But it was clear from the result of the other appeals that there had never been a basis for the case.