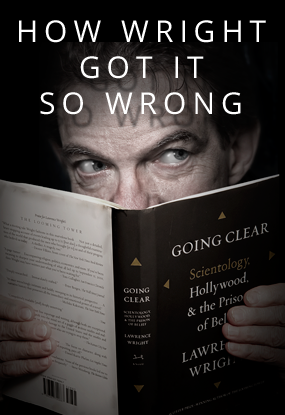

A Correction of the Falsehoods in Lawrence Wright's Book on Scientology

“The exposé [Time magazine, May 1991] revealed that just one of the religion’s many entities, the Church of Spiritual Technology, had taken in half a billion dollars in 1987 alone.

”>> True Information: The figure stated in the Time article by Richard Behar was $503 million. The correct 1987 Church of Spiritual Technology revenue figure was $4 million. In other words, Richard Behar misreported the figure by almost half a billion dollars. Behar had the figures available to him in public records and still reported what was blatantly false.

In all, Wright relies on Behar half a dozen times. The May 6, 1991 issue of Time magazine contained a vitriolic and sensationalized attack upon the Scientology religion, the Founder, its management, its practices and parishioners. Time made no pretense of balance in its presentation, leading one of its readers to write that Time’s “inability to find anything good to say about a rapidly growing international organization … leads me to conclude that this is a case of slanted journalism for unstated motives.”

The false premise of the article stemmed from its corrupt conception. The pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly was feeling the economic consequences of Scientology’s opposition to psychotropic drugs and its exposure of the drug Prozac’s deadly side effects, a position that has now borne out to be chillingly accurate. Lilly sponsored Behar’s libel, purchasing hundreds of thousands of reprints before the issue of Time was published. Richard Behar’s story was bought and paid for in advance, a fact that Time and Lilly have never denied.

The Time article provoked multiple lawsuits. Four years after the article was published, United States District Judge John E. Sprizzo told Time’s lawyer, “given the obvious bias and hostility he [Behar] had toward the Church of Scientology … you would be better off if someone else had written this article.” That judge presided over a case brought by a Church parishioner who was defamed in the article. The case was settled and as part of that settlement, Time published a correcting entry in the November 11, 1996 issue of Time.

The Church of Scientology International sued its former public relations firm, Hill and Knowlton (H & K), for abruptly canceling the Church’s account immediately after the article came out under pressure from Lilly. The case settled on terms that are confidential.

The Church also brought suit against marketing consulting company Trout and Ries, Inc., over remarks made in the article by Jack Trout, president of the company. The Church settled the matter on favorable terms.

Two other sources for the article, Glover and Dee Rowe, failed to persuade a California court to award them millions in damages, based on false allegations against the Church substantially identical to those which they had spread in the Time article.

Another source of Time’s article, Peter Georgiades, was obliged to settle a lawsuit with a company owned by a Scientologist. The company had filed suit based on the remarks Georgiades made in Time Magazine.

What other facts did Behar get wrong?

Behar reported as fact a false accusation against the Church for which the source of the allegation was serving a federal prison sentence for obstruction of justice for making the very same false claim to the FBI. In 1988, the individual was indicted for eleven counts of mail fraud. In defense, he invented a claim that he had been put up to his crime by the Church. He even hired someone to make a threatening call to himself pretending to be from the Church. Already sentenced to five years for the mail fraud, when the plan unraveled, the government added six months to his prison term for obstruction of justice. Behar knew all this; he interviewed the man in his prison cell. Yet Behar printed as fact the very same false claim for which the individual was sent to jail for making.

Behar relied on then executive director of the Cult Awareness Network as a source of false statements about Scientology and its expansion for his article. The Cult Awareness Network (CAN) was a group with executives and members who had proven criminal backgrounds and affiliations. One president, Michael Rokos, resigned in late 1990 amid public exposure of a 1982 criminal conviction for soliciting lewdness, i.e., making a perverted sexual proposition to an undercover policeman. Rokos resisted arrest and also gave a false name to the police. CAN served as a networking and referral service for the “deprogramming” racket. CAN encouraged individuals to pay tens of thousands of dollars to kidnap family members, hold them against their will, and physically and mentally harass them until they are forced to denounce their religious beliefs. In 1996, CAN closed its doors after a multi-million dollar civil judgment from one of its deprogramming victims bankrupted it.

Behar accused the Justice Department of failing to “back the IRS and the FBI in bringing a racketeering suit against the Church because it was unwilling to spend the money required to take the organization on.” The true reason why the Justice Department refused to support the IRS was discovered later when Freedom of Information Act documents were released. A FOIA document revealed that the Justice Department rejected the IRS’s request for prosecution because the case was so weak, specifically and in part, on an evaluation that the IRS witnesses received the lowest possible credibility rating.

Behar claimed that “Scientology managers” were pocketing millions of dollars when a two year comprehensive examination by the Internal Revenue Service found that all funds collected by Churches of Scientology were used exclusively for charitable and religious purposes. Even at the highest levels of the Church structure, Scientology executives receive salaries that are significantly lower than those of the leaders of other religious organizations. These executives are all very dedicated Scientologists who work an average of 15 hours a day, usually seven days a week. They live in small apartments provided by the Church. All high-level Scientology executives share communal dining arrangements with numerous other staff members. Most of them do not even own a car. They devote their abilities and energy to the expansion of the religion. It is for these reasons that Behar was unable to name a single specific case of a Scientology executive enriching himself.

Behar described L. Ron Hubbard’s writing career as “modestly successful.” L. Ron Hubbard was one of the early Science Fiction Greats. As such, Mr. Hubbard was in the company of other great authors of science fiction, such as Robert Heinlein, A.E. Van Vogt and Isaac Asimov. The popularity of L. Ron Hubbard’s works has continued through the decades to this day. His books regularly receive rave reviews, appear repeatedly on best seller lists around the world, and are in great demand. L. Ron Hubbard has been awarded four Guinness World Records for his writing accomplishments and for the continued popularity of his writings, hundreds of millions of copies of which are in circulation:

Most Published Works by a Single Author: 1,084

Most Translated Author in the World: 71 languages

Most Audio Books Titles on Earth: 185

Most Translated Nonreligious Work—The Way to Happiness: 97 languages.

Behar claims that the Church of Scientology did not go “religious” until 1971. He wrote in reference to a 1971 court decision, Behar alleged that, “Hubbard responded by going fully religious, seeking First Amendment protection for Scientology’s strange rites,” implying that Scientology was not a religion prior to that point. This allegation is patently false. Scientology has been a religion since the incorporation of the first Church in 1954. The religious nature of Scientology has been the subject of many articles by its Founder since that time. Behar completely twisted the facts concerning a 1971 U.S. District Court decision which held that Scientology “is a bona fide religion and that the auditing practice of Scientology and accounts of it are religious doctrine.” The U.S. District Court based its ruling on the findings of the Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia Circuit that had fully evaluated the Scientology religion two years earlier and found it to be bona fide in every respect. The court stated, “On the record as a whole, we find that appellants have made out a prima facie case that the Founding Church of Scientology is a religion. It is incorporated as such in the District of Columbia. It has ministers, who are licensed as such, with legal authority to marry and to bury. Its fundamental writings contain a general account of man and his nature comparable in scope, if not in content, to those of some recognized religions.”

These and other falsities in the article were clearly and broadly made known by the Church as part of a public campaign including full page ads and a magazine correcting the articles’ false reports and exposing the agenda behind the article (The Story That TIME Couldn’t Tell). Wright ignored all of this. Thus, it is far from surprising to find Richard Behar in company with Lawrence Wright and his other anti-Scientology sources sharing stories of their tribulations on the Internet.