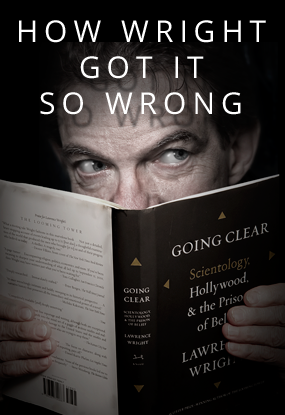

A Correction of the Falsehoods in Lawrence Wright's Book on Scientology

Wright introduces the argument that Scientology in general and the RPF in particular are the same as the Chinese torture and brainwashing of American prisoners during the Korean war.

“The question posed by Prince’s experience in the RPF is whether or not he was brainwashed. It is a charge leveled at Scientologists, although social scientists have long been at war with each other over whether such a phenomenon is even possible. The decade of the 1950s, when Scientology was born, was a time of extreme concern—even hysteria—about mind control. Robert Jay Lifton, a young American psychiatrist, began studying victims of what Chinese Communists called “thought reform,” which they were carrying out in prisons and revolutionary universities during the Maoist era; it was one of the greatest efforts to manipulate human behavior ever attempted.”

>> True Information: To support his anti-religious bias Wright advances a theory that has no currency in the scientific community, except in the closed loop of anti-religious propagandists. In 1987, the American Psychological Association rejected applying Lifton’s theories to religious experience as having no scientific basis.

The staunchest proponent of applying Dr. Lifton’s theories to religious experience was the late Dr. Margaret Singer of Berkeley. She had been a clerk in the early studies of American prisoners of war in Korea who had been physically coerced by violence, threats, and physical punishment into denouncing the American position in the war. In the 1980s she sought to capitalize on the false hysteria surrounding new religions by expanding this theory to apply to the voluntary participation of people into new religious movements.

On May 11, 1987, the Board of Social and Ethical Responsibility for Psychology of American Psychological Association (APA) formally dismissed Singer’s notions of thought reform and coercive persuasion after she and several of her associates had formed a task force within the APA on “deceptive and indirect methods of persuasion and control” and had submitted a report. The APA Board stated that “In general, the report lacks the scientific rigor and evenhanded critical approach needed for APA imprimatur.” The APA Board warned the task force members not to imply that the APA in any way supported the positions they had put forward.

On May 1, 1989, several members of the APA, the American Sociological Association, the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, and individual sociologists reiterated the APA’s position in a brief to the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of Holy Spirit Association for the Unification of World Christianity v. David Molko and Tracy Leal, in which they argued that Singer’s theories of religious brainwashing have “no scientific validity. No methodologically sound studies support the theory, many refute it.”

Dr. Lifton himself had serious reservations about using his theories in litigation against new religious movements. Dr. Lifton observed in 1987 that the participation in religious movements at odds with the prevailing staus quo is:

“not primarily a psychiatric problem, but a social and historical issue…. I do not think that pattern is best addressed legally…. Not all moral questions are soluble legally or psychiatrically, nor should they be. I think psychiatrists and theologians have in common the need for a certain restraint here, to avoid playing God and to reject the notion that we have anything like a complete solution that comes from our points of view or our particular disciplines.” [R. Lifton, The Future of Immortality and Other Essays for a Nuclear Age, 218-219 (1987).]

Since the APA’s rejection of their findings, Singer and her disciples were prohibited by several courts from testifying as experts concerning their discredited theories of “coercive persuasion.” For example, in 1989, Singer and her theories were rejected by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, noting that the plaintiff in the case “failed to provide any evidence that Dr. Singer’s particular theory, namely that techniques of thought reform … has a significant following in the scientific community, let alone general acceptance.”

As noted above (see entry for page 125), the Rehabilitation Project Force (RPF) is a voluntary program of redemption undertaken by members of the Church of Scientology’s religious order, the Sea Organization, who have been found to have committed offenses that otherwise would warrant their dismissal from the order. It consists of daily periods of study, religious counseling, and physical tasks working as a team with other members. Participants receive adequate food and sleep to enable them the benefit from their studies and spiritual counseling.

Moreover, religious scholars who have examined the program have determined that it is similar to—and in many ways less stringent than—programs run by religious orders of other religions. [The Sea Organization, A Contemporary Ordered Religious Community by Professor J. Gordon Melton; The Church of Scientology’s Rehabilitation Project Force, A Study by Professors Pentikäinen, Redhardt and York; and Expertise of Dr. Frank Flinn]

Dr. Melton notes that Catholicism and Buddhism have ethical standards similar to the Sea Organization’s, but that in Scientology, unlike these religions, one can earn a second chance to remedy violations of religious order rules. “Sea Organization’s system differs from that of both the Roman Catholic and Buddhist systems in that it offers a means for those judged guilty of expulsion offenses to redeem themselves and be reintegrated into the community.”

Dr. Melton notes that the physical labor requirements also are not unlike those of other religions, notably Buddhism. “It is reminiscent of the work (‘chop wood, carry water’) that is often integrated into the longer Zen Buddhist retreats. Work remains an integral part of the daily life of Zen monks and nuns, and visitors to a Zen monastery for retreats or short stays will be scheduled to participate in the workday that might include cooking, chopping wood, heating water, working in the fields, and cleaning.”

A noted scholar of comparative religion and former Franciscan monk, Dr. Frank K. Flinn, now Adjunct Professor in Religious Studies at Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, undertook an examination of the RPF program as part of an independent study he conducted on Scientology.

Dr. Flinn notes:“It is my opinion that spiritual disciplines and practices such as the Rehabilitation Project Force of the Church of Scientology are not only not unusual or even strange but characteristic of religion itself when compared with religious practices around the world. Contrary to the generally second-hand opinions of outsiders and to the claims of disaffected members, whose motives are suspect, I would say that submission to such practices … follows as a natural consequence from a free religious commitment to a spiritual discipline in the first place.”

Dr. Flinn writes that physical labor is a daily activity in Roman Catholic monasteries for both men and women and consists mainly of gardening, woodworking, washing laundry, running and repairing farm equipment, harvesting and preparing food for the monastery. Those who have chosen the religious life undertake such rigors willingly, even as Dr. Flinn did himself as a Franciscan initiate:

“Contemplatives, monks and mendicants and other religious societies not only take the three vows mentioned above, but also commit themselves to other religious practices such as long hours of meditation each day, periods of manual labor, midnight choir (the singing of Psalms), fasting during Lent and Advent, study of the rule of the order and other spiritual writings, and silence. As a member of the Franciscan order (which I left voluntarily and was free to do so), I myself freely submitted to the religious practice of flagellation on Fridays, striking the legs and back with a small whip to mortify the desires of the flesh and to commemorate the flagellation of Jesus Christ before his crucifixion. In the tradition of St. Benedict’s dictum ora et labora (Latin for pray and work), I also spent several hours each day, with the exception of Sunday, doing physical labor, including woodworking, tending a garden, cleaning floors, washing laundry, peeling potatoes, etc. These tasks were assigned to me by my superiors, and because I took a vow of obedience, I did them. Furthermore, as a mendicant, I took a vow of absolute poverty such that I owned absolutely no material possessions, including the robe which I wore. When rules of the monastery are broken, monks and friars are regularly assigned menial tasks as penances. Compared with these Roman Catholic practices, the practices of the RPF are not only not bizarre but even mild.”

As Professor Flinn points out, similar practices exist in Jesuit Orders and in some eastern religions such as Hinduism.

Likewise, Professors Pentikäinen, Redhardt and York note the similarities of the RPF with programs operated by other world religions:

“The dietary requirements and conditions of interaction with non-members etc. are carefully defined, and here again, the RPF programme has many resemblances to the systems of other religious traditions. As far as other world religions are concerned, specific similarities may be found in another ascetic religion—Buddhism. One RPF member made such a comparison and Mr. Hubbard placed importance and value on Buddhist tradition by citing and reprinting a Buddhist text on ethical standards and the rehabilitation of a monk years before the RPF programme was initiated.

“Certain Buddhist and Christian monastic orders require an erring member to complete a regimen of exercise and training, as defined by the order, before re-admittance as a full member. These processes may include in- depth reading and study of the principles of the religion, physical work and training, meditation and other spiritual exercises, and possibly also a period of hermetic contemplation.

“From the interviews, it was apparent that the participants had much greater opportunity to concentrate on their spiritual counseling in the RPF than in their previous careers in the Church of Scientology. In seclusion, as it were, they were able to withdraw from the hustle and bustle of everyday life and focus on achieving redemptive goals. This concept, of course, is a traditional one. Within Christianity there are hermits called anchorites who withdraw from society to devote themselves to prayer and penance.” [RPF Study, Pentikäinen, et al.]